Thinking Beyond Your “Why”

If you are in the business world, you have undoubtedly heard of Simon Sinek. Even if you have never read his books, you have probably watched one of...

This winter, during a severe depressive episode, I mass-applied to an uncountable number of volunteer positions in my home city of Vancouver, BC.

I had no specific cause or organization in mind. In truth, I only wanted a few hours every week where I had to think about something other than myself, my job, my art, my friends, my silly little problems.

I applied to clean shorelines. Teach English to refugees. Host a beauty night at a women’s centre. Marshal at protests. Pass out Naloxone kits in the Downtown Eastside. Clean dorm rooms at a shelter.

The last organization I applied to was called The Writers’ Exchange; a weekly after-school literacy program where volunteers read with kids from schools in the Downtown Eastside.

It was the last position on my list for a reason. Multiple reasons, actually.

First: I’ve never been big on children. To be frank, I always found them boring. Or maybe it would be more accurate to say I assumed the things that most interested me weren’t interesting to them.

And second: I feared the very thing making me most depressed — the bleakness of our world and my increasing inability to imagine a livable future within it — would be exacerbated by spending more time with its heritors.

So, when I received an email invitation to attend an orientation meeting, I was less than enthusiastic.

Still, I showed up. I’m not sure why. I just was depressed and needed to feel like I was doing something right.

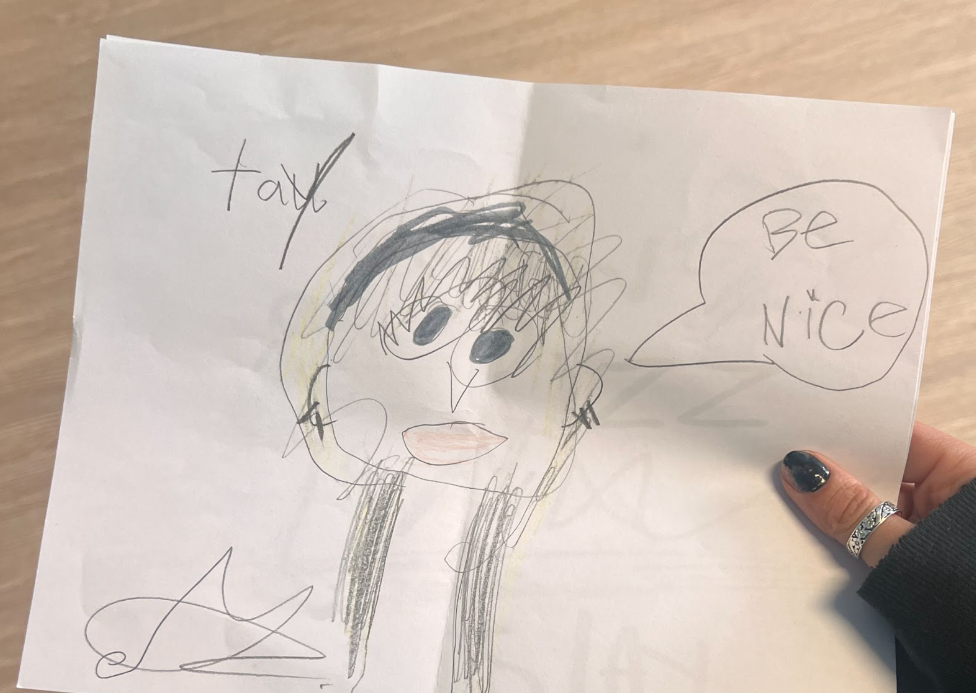

I sat in a semi-circle in a room full of primary colours and children’s artwork. In addition to the regular literacy program, I learned that volunteers help students write their own stories and poems. At the end of the term, these stories and poems are published in a print journal.

I’m ashamed to admit I had low expectations for their work. I couldn’t remember reading anything written by children since I was a child myself. And I hadn't given much thought to the value of these little, untrained, and inexperienced voices.

I asked myself: what is the point of writing? Of publishing and record-keeping? Silly me, I thought I already knew the answer.

Then, after leaving orientation, I remembered a poem we read in my undergraduate poetry workshop: “One of Us” by Joyce Sidman.

You should read it too. Here it is:

“That kid is weird,” says

the teacher, flipping her shining hair.

“I don’t know where he’s at.”

Indeed, he is quiet

in the way of a giraffe:

ears tuned to something we can’t hear.

He turns his sleepy eyes on me—

chocolate brown

with long, extraordinary lashes—

as I hand him a seashell:

something to write about, you know,

something to focus on.

Suddenly, silently,

in the mysterious way of poetry,

he is at

that shell,

he is in it,

his heart fills up with it.

O Shell, he writes,

you make lizards dance

in the sky with birds.

Never leave me, Shell.

During sharing time,

he reads his poem aloud—

reverently,

almost to himself.

Half the class is stunned,

half embarrassed.

The teacher shakes her head.

I am barely breathing.

One of us, I sing, one of us!

Something about the boy’s poem, though I couldn’t put my finger on it, stuck with me throughout the years. Lizards dancing in the sky — it meant very little, maybe nothing at all, and yet I felt something wonderful in my body when I envisioned it.

My first day in the program was a few weeks later. I met a girl in grade three named Adriana. My program coordinator, Sasha, explained that Adriana had been coming to the Writers’ Exchange for a few years now. She could be “a handful”, according to Sasha, but she was also incredibly bright, funny, and cheerful.

In the first few hours of knowing me, Adriana told me about her favourite subject (science) and her very smart little brother. She loved Ice Spice and had a crush on a boy from a neighbouring school. She hated swimming. Loved small dogs. Her parents were refugees who came to Vancouver while Adriana’s mother was still pregnant with her. She never wanted to visit her home country, because her parents weren’t safe there.

Adriana was a handful. She was bright, funny, and cheerful. And she was an incredible storyteller.

Over the weeks, she’s told me countless stories about her home country. Violent stories. Stories she couldn’t possibly remember, yet she swears on her brother’s life that she does.

She once told me a story about a house fire in the town her mother lived in right before she came to Canada. “It was the hottest fire I’ve ever felt,” she said as we walked the few blocks from her school to the Writers’ Exchange.

“How did you feel it?” I asked her. “You weren’t even born!”

She told me she felt the heat from inside her mother’s belly.

One of us, I sang, one of us!

The thing that strikes me most about Sidman’s poem is that, nearly five years later, I didn’t actually remember her poem at all. I was convinced that: “O Shell, / you make lizards dance / in the sky with birds. / Never leave me, Shell.” was the poem we studied. That weird kid’s poem. And without even trying to, I had memorized it, word for word. That’s the kind of impression it left on me.

It was only after Googling the lines (for this blog post) that I realized his poem was framed within the context of Sidman’s perspective in “One of Us”.

There are multiple reasons a writer might use a frame narrative technique in their work, but the most common is to highlight the differences between two or more time periods, usually the past and the present.

In the case of Sidman’s poem about the weird boy’s poem, the framed narration implies a prophecy. Sidman recognizes a potential future for the boy. One where his peculiarity is cherished and celebrated, as hers is.

As she writes the poem, and as we read it, we make that future real.

It’s been two months since I started volunteering at The Writers’ Exchange. Every week, I am in raptures with Adriana’s stories. Her imagination. Her capacity to convey complex feelings with imagery. The absolutely fascinating way she frames her parents’ experiences through her own remarkable perspective.

Another thing about Sidman’s poem: I’ve been every character. The weird kid, the speaker who recognizes his brilliance, and, as much as I hate to admit it, the dismissive, unseeing teacher.

Here’s the part I was missing:

Children, though we try desperately to save them from it, live in the same world as us. They see the horrors we see. They hear the same songs and pet the same dogs and feel the same heat.

And as gut-wrenching as it is to accept, they understand what it means.

In a standard frame narrative, this is the part where the writer ties everything up. Offers a zoomed-out, big-picture resolution for what it all means.

But I can’t do that. The future is still unspooling before me and you and Adriana and her parents and all of us. On good days, it looks messy. On bad days, downright grotesque.

So why do I keep going back to The Writers’ Exchange? What’s the point of listening to Adriana’s stories? Of helping her put them into writing?

All I know is that I want to make lizards dance in the sky with birds. I want to find the answer.

.png)

If you are in the business world, you have undoubtedly heard of Simon Sinek. Even if you have never read his books, you have probably watched one of...

.png)

Nearly every morning, I have hypnopompic dreams about phone notifications.

When you become a parent, you have all these hopes and dreams for your child's future.