OpenAI and Gates Foundation Bet $50 Million on AI for African Primary Care

OpenAI and the Gates Foundation announced Tuesday they're committing $50 million to deploy AI tools across 1,000 primary healthcare clinics in Africa...

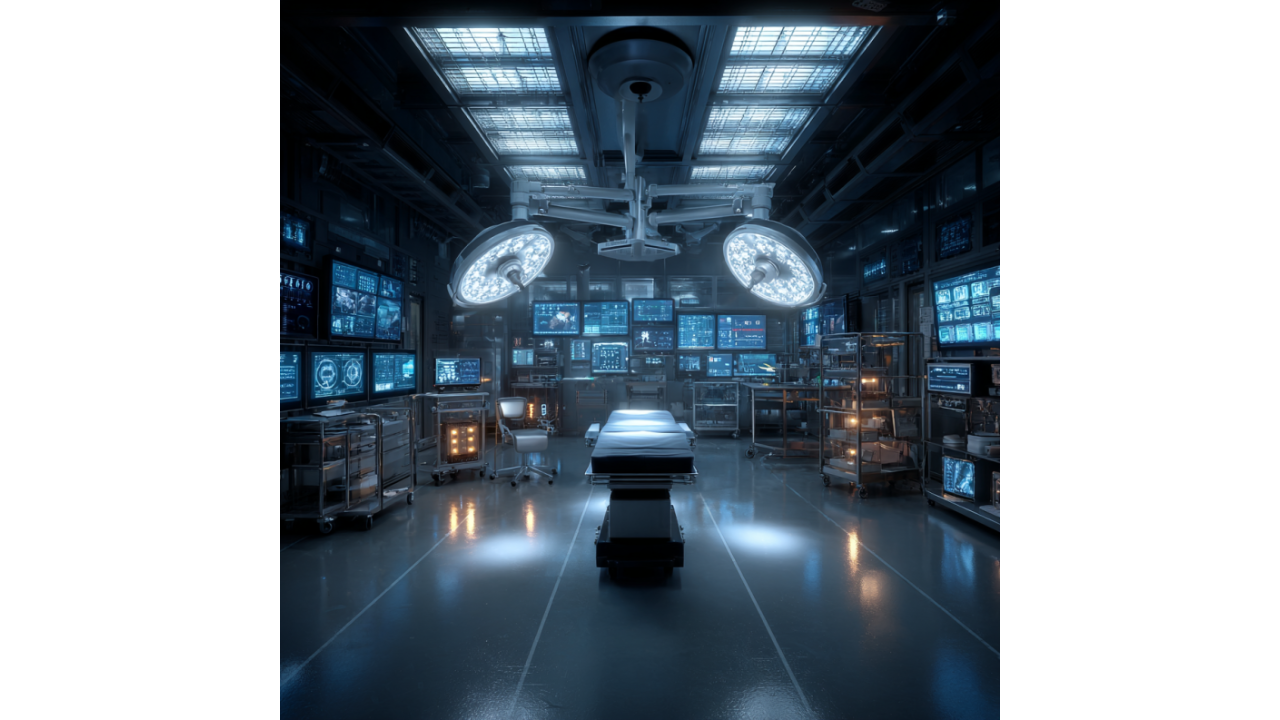

Akara, a startup building "air traffic control for hospitals," landed on Time's Best Inventions of 2025 list by tackling a problem nobody's hyping but everyone's paying for: operating room coordination. Two to four hours of OR time disappear daily—not from surgeries, but from scheduling chaos, manual coordination, and guesswork about room turnover.

Co-founder and CEO Conor McGinn told TechCrunch's Equity podcast that while healthcare buzzes about AI and surgical robots, the actual money drain is logistical inefficiency. Akara uses thermal sensors and AI to create ambient sensing systems that document surgeries without privacy concerns, functioning like flight tracking for surgical workflows.

This is healthcare AI that solves operational problems rather than chasing sci-fi visions of robotic surgeons. Whether it actually works at scale remains to be proven, but at least they're targeting real costs instead of imaginary bottlenecks.

Akara started building cleaning robots—the sexy healthcare automation everyone assumes hospitals need. They pivoted to ambient sensing after realizing the real bottleneck isn't robotic capability, it's infrastructure coordination enabling any automation to function effectively.

McGinn identifies this as healthcare's actual limitation: not the robots themselves, but the operational systems required to deploy them. Surgical robots exist. What doesn't exist is reliable coordination ensuring ORs are ready, staff are positioned correctly, equipment is available, and transitions between cases happen efficiently.

This mirrors broader AI deployment patterns: the technology often works in controlled environments, but integrating it into messy real-world workflows with legacy systems, human coordination requirements, and institutional inertia remains the hard problem. Akara bets that solving coordination creates more value than adding robotic capabilities to uncoordinated environments.

That's probably correct—but also less fundable, less impressive in demos, and harder to explain to investors expecting futuristic robot videos rather than scheduling optimization software.

Akara's technical approach uses thermal sensors instead of cameras to track OR activity. Thermal imaging documents workflows, measures room turnover, and provides data for AI optimization without capturing identifying visual information that triggers HIPAA concerns and staff resistance.

This is genuinely clever product design: achieve the surveillance-level data capture required for operational optimization while avoiding the privacy and regulatory complications of video recording. Staff can't object to being filmed because they're not being filmed—just tracked as thermal signatures moving through space.

The limitation: thermal sensors capture presence and movement, not detailed activity. You can track how long rooms stay empty, how many people are present during procedures, and when turnover delays occur. You can't see what's actually causing delays without supplemental data sources or manual classification.

Whether thermal-only sensing provides sufficient granularity for meaningful optimization versus requiring additional instrumentation remains an implementation question. But the privacy calculus is smart—remove the objection point that kills adoption before proving value.

McGinn describes NHS vetting as a "backdoor into U.S. hospitals"—an interesting go-to-market strategy. Get validated by the UK's National Health Service, use that credibility to access risk-averse US hospital administrators who prefer externally-vetted solutions over experimental startups.

This reveals realistic understanding of healthcare sales cycles: nobody wants to be first, everyone wants to be second. Having NHS deployment provides the reference case that makes US adoption feasible. It's also slower than direct US market entry, but potentially more sustainable by building credibility before facing the full complexity of American healthcare procurement.

The approach acknowledges that healthcare innovation diffusion follows different patterns than consumer tech—trust, validation, and institutional backing matter more than feature velocity or funding announcements. Akara is playing the long game rather than chasing rapid deployment metrics that look good in pitch decks but don't translate to sustainable adoption.

McGinn mentions 40% of the nursing workforce could leave within five years—a staffing crisis that makes operational efficiency from necessity rather than optimization. If hospitals lose nearly half their nursing staff, they can't maintain current operational models even if they wanted to.

This creates forcing function for automation: not because technology is ready, but because human workforce availability won't support existing workflows. The question becomes whether automation can actually absorb the gap or whether healthcare quality degrades as understaffing overwhelms whatever efficiency gains technology provides.

Akara's bet: operational coordination improvements can stretch remaining staff further by eliminating wasted time between procedures, reducing coordination overhead, and optimizing resource allocation. That's more credible than "robots will replace nurses"—you're not replacing clinical judgment, you're eliminating administrative friction.

But it also means automation needs to work reliably enough that stretched staff can depend on it rather than creating additional cognitive load from unreliable systems requiring human backup. The margin for error shrinks when you're operating at reduced capacity.

Operating room time is extraordinarily expensive—facilities cost, staff salaries, equipment amortization, and opportunity cost of procedures that could run instead. Two to four hours daily of coordination inefficiency across thousands of hospitals represents billions in annual waste.

If Akara's system recovers even one hour per room per day, the ROI is immediate and measurable. This is the ideal enterprise software value proposition: clear cost reduction with definable payback period and minimal implementation risk.

The challenge: hospitals operate at capacity constraints where recovering OR time doesn't automatically translate to revenue unless they have patient demand to fill it. In overloaded systems, efficiency gains increase throughput. In capacity-limited systems, they just reduce overtime and rush fees—still valuable, but smaller financial impact.

Akara needs to target hospitals with patient backlogs where OR availability is the constraint on volume. For facilities already struggling to maintain current caseloads due to staff shortages, coordination efficiency might just mean staff work slightly less unsustainably rather than dramatically increasing surgical volume.

McGinn's core insight: medical robotics is held back not by robotic capability but by infrastructure to coordinate them. This inverts the typical healthcare automation narrative focusing on clinical AI and surgical robots while treating operational systems as solved problems.

If true, it means billions in robotics investment won't deliver proportional value until someone solves the boring coordination problems. It also means Akara's opportunity is time-limited—once they demonstrate value, larger healthcare IT vendors will build or acquire similar capabilities.

The defensibility question: what prevents hospital systems from replicating this functionality once it's proven valuable? Thermal sensor deployment isn't proprietary. AI coordination algorithms aren't secret. First-mover advantage in healthcare is real, but sustainability requires either network effects (multi-hospital coordination), data advantages (better models from more deployments), or integration lock-in (becoming embedded in hospital workflows).

Akara probably knows this, which is why NHS validation matters—establish credibility and reference cases before competition emerges, then race to deploy broadly enough that switching costs protect market position.

The pitch is compelling: solve real problems causing measurable costs, use technology that addresses privacy objections, target pain points so acute that adoption becomes inevitable rather than discretionary.

The execution risks: healthcare IT implementations fail constantly despite perfect logic. Hospitals resist operational changes even when beneficial. Staff pushback kills systems regardless of administrator enthusiasm. Integration with existing scheduling and EHR systems creates complexity vendors underestimate.

Akara being on Time's Best Inventions list means they've demonstrated enough traction for legitimacy. It doesn't guarantee they've solved the hard parts of scaling across diverse hospital environments with different systems, workflows, and constraints.

But they're solving a problem that actually exists and costs money people can measure. That puts them ahead of most healthcare AI companies promising clinical breakthroughs that remain perpetually five years away.

If you need help evaluating healthcare technology implementations beyond vendor claims or building operational efficiency strategies around infrastructure improvements rather than futuristic robotics, Winsome Marketing focuses on solutions that address today's costs.

OpenAI and the Gates Foundation announced Tuesday they're committing $50 million to deploy AI tools across 1,000 primary healthcare clinics in Africa...

Google Health AI just released MedASR—an open-weights speech-to-text model specifically trained on 5,000 hours of physician dictations and clinical...

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services just announced a $2 million prize for AI tools that will help caregivers manage the crushing burden...